[ad_1]

India, already the world’s fastest-growing major economy, is pushing for even more dramatic expansion to become a developed nation, a goal that hinges on expanding access to capital.

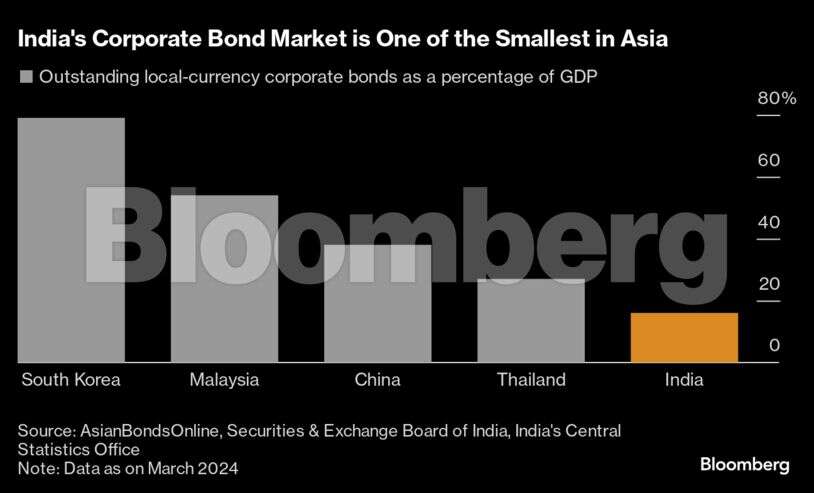

Nothing illustrates that challenge better than the 47 trillion rupee ($559 billion) corporate bond market. It’s one of the world’s smallest as a percentage of gross domestic product, at just 16%, even after record growth. Bankers in Mumbai say doubling that ratio would better help finance ambitious goals, like becoming a $5 trillion economy in the next three years.

One of the major impediments is a longstanding rule from authorities that makes it hard for long-term investors like insurers and pension funds to go big on infrastructure. The regulation bars them from investing in notes rated below AA, which in India are deemed risky because they’re hard to offload in a smaller market during times of stress.

Spending on roads, ports and bridges, as well as on all kinds of capital expenditure, is set to reach about 110 trillion rupees ($1.3 trillion) between 2023 and 2027, an increase of 70% from the previous five years, according to the National Stock Exchange of India. The company notes market will likely cover just one-sixth of that amount, it said. That’s due in part to those restrictions, given many infrastructure borrowings carry lower or no ratings.

“The corporate bond market is not deep enough to support the country’s infrastructure finance requirement,” said R Shankar Raman, director and chief financial officer at Larsen & Toubro Ltd., India’s top engineering company. For these reasons, the firm has tended to rely mainly on its own cash and bank loans for funding, and has only tapped the bond market once in the past four years.

Government financing of course plays a major role in the infrastructure projects dotting Indian cities. But as the economy gets even bigger, the need for both the local credit market and overseas lenders to offer alternative funding sources will become more acute.

The subways, airports, sanitation and electricity grids underpinning urbanization in the world’s most populous nation take years to build. Such time horizons attract investors like insurers who need cash flows that match their longer-term payouts. But in India the regulatory hurdles have disrupted this dynamic.

Insurers are also subject to a cap on their exposure to infrastructure assets. For instance, they cannot invest more than 20% of the cost of the project.

“The rules clearly deserve a relook,” said Somasekhar Vemuri, senior director regulatory, affairs and operations at Crisil Ratings Ltd., a local unit of S&P Global Ratings. “There can be guidelines based on the investor’s risk capital to avoid concentration risk rather than linking the exposure limit to the issuer’s capital base.”

A spokesperson for the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India, the industry watchdog, said that the authority will continue to review investment measures and look at any innovative debt instruments that would enable infrastructure funding.

A representative at the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority didn’t immediately reply to a request for comment.

There has been some progress. That follows steps spanning recent years up to just the past few days— measures that stand to strengthen the bond market and wean companies off bank borrowings. Those include:

- The securities regulator on Wednesday introduced a measure to boost liquidity in the secondary market for company bonds

- In April, the Securities and Exchange Board of India shifted to allow borrowers to privately place bonds with face values as low as 10,000 rupees, in an effort to boost retail investor participation. The previous threshold was 100,000 rupees

- In 2022, SEBI took a step to enhance liquidity in the bond market, by encouraging bigger outstanding issuance sizes of the kind that are more easily traded. It made it compulsory for companies to have no more than nine conventional bonds maturing within a given year, which effectively encouraged them to tap existing securities, increasing their overall size

- Earlier, in 2016, borrowers were required to issue privately placed notes using an electronic book platform to improve price discovery and reduce costs

- Companies have already raised almost 8.6 trillion rupees selling bonds in 2024, set for a second record year. Banks and shadow financiers are leading the expansion amid a double-digit spurt in loan demand.

At the same time, companies helping to fuel India’s expansion also have other debt financing options. Some prefer local loans. The amount of such lending to industries and services stands at about 28% of GDP.

What would be one of the largest local-currency deals in India this year highlights the reliance on loans for key infrastructure. State-owned Bharat Petroleum Corp. is in talks with lenders to raise about 320 billion rupees for building a refinery.

A unit of Indian Oil Corp. is also targeting a 280 billion rupee facility for a similar project.

Loans are often more practical to finance projects than bonds as the money can be drawn in phases, unlike bonds where the funds would sit idle until needed, according to Vetsa Ramakrishna Gupta, director finance at BPCL.

Yet, expanding the bond market remains crucial, as it allows lenders to spread out credit risks. Also, the yields are more sensitive to shifts in policy rates, meaning any central bank rate cut would filter down more quickly.

There are signs of greenshoots as some new lenders that finance infrastructure tap the bond market steadily, said Sujata Guhathakurta, president and head of debt capital markets at Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. in Mumbai.

“If the investment rules are relaxed a bit, then investor appetite will improve resulting in the bond market to deepen and grow further,” she said.

[ad_2]

Source link